The view of the Medicine Bow Mountains near Walcott, Wyo. (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

WALCOTT, Wyo. — I’ve never been to Montana to see Big Sky Country but from the looks of the things, Wyoming could rightfully claim that title, too. On my way west from Laramie, I could have simply stuck to Interstate 80 and taken a shorter route through the southern tier of Wyoming.

But the Lincoln Highway bends north, roughly following the Union Pacific Railroad around the Medicine Bow Mountains before eventually rejoining I-80 to cross the Great Divide Basin. Many Lincoln Highway enthusiasts are adamant about taking the old, slower route. I can see why.

Thus far along my trek, this stretch of land might be the most impressive geography along the route. And this is where the combination of light, sky, clouds and topography were finally in harmony and my smartphone was able to capture the true grandeur of the territory.

Post continues below …

Looking southwest along the Lincoln Highway near Walcott, Wyo. (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

Because I was off I-80, I had an easier time making brief pitstops to enjoy this landscape. I was also mostly alone out here — passing cars were few and far between — so I essentially had this beautiful land all to myself.

In Travels With Charley, John Steinbeck wrote:

From the beginning of my journey, I had avoided the great high-speed slashes of concrete and tar called “thruways,” or “superhighways.” … These roads are wonderful for moving goods but not for inspection of a countryside. You are bound to the wheel and your eyes to the car ahead and to the rear-view mirror for the car behind and the side mirror for the car or truck about to pass, and you must read all the signs for fear you may miss some instructions or orders.

An abandoned school in Bosler, Wyo. (Photo by Flickr user afiler via CC BY-SA 2.0 >>)

This original route travels through the mostly abandoned settlement of Bosler, where, according to American Road, “the last souls packed up and left, leaving a ghost village of empty mobile homes and scrawny shacks” when I-80 opened in 1971.

I can understand why economics would drive most people out of this great land. And part of me is thankful that it did so I could enjoy this expanse on my own with few distractions.

There are, for sure, many places like this across the American West, but I want to think that this part of Wyoming could be the greatest, grandest and most impressive territory that anyone seeking to understand the power of emptiness could ever discover.

This is a beautiful place. (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

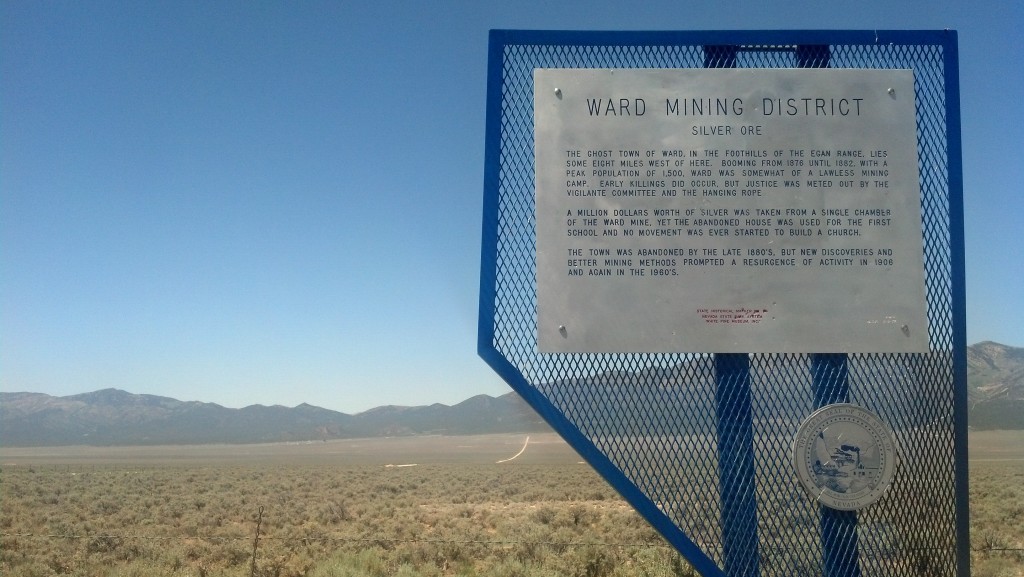

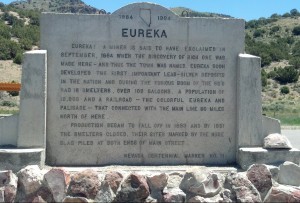

EUREKA, Nev. — This place might be the best example of an old mining town anywhere along the Lincoln Highway.

EUREKA, Nev. — This place might be the best example of an old mining town anywhere along the Lincoln Highway.