At a rest area along east of Laramie, Wyo., a towering statue of Abraham Lincoln is visible from Interstate 80. (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

LARAMIE, Wyo. — Heading westward from Iowa, there are fewer and fewer signs marking the route of the Lincoln Highway. This is especially true in Wyoming, where significant sections of Interstate 80 west of Cheyenne were simply built over the original Lincoln Highway.

LARAMIE, Wyo. — Heading westward from Iowa, there are fewer and fewer signs marking the route of the Lincoln Highway. This is especially true in Wyoming, where significant sections of Interstate 80 west of Cheyenne were simply built over the original Lincoln Highway.

But Wyoming is home to a gigantic Abraham Lincoln monument along the route at the highway’s highest point, 8,835 feet at the Summit Rest Area on Sherman Hill.

The 16th president’s bust looks down on Interstate 80 from the top of a tall column built out of stones. The sound of the highway echos up to the Lincoln statue, especially as the sputtering of truck engine brakes cuts across the monotone hum of vehicular traffic.

According to RoadsideAmerica.com:

Lincoln’s head was built by Wyoming’s Parks Commission to honor Lincoln’s 150th birthday. It was sculpted by Robert Russin, a University of Wyoming art professor and a Lincoln fan (When he died in 2007, his ashes were interred in the hollow monument). The head originally was perched at Sherman Summit, 8,878 feet above sea level, the highest point along the old coast-to-coast Lincoln Highway. When I-80 was completed in 1969, the head was moved here — losing a couple of hundred feet (and any eponymous rationale for existing, really) but gaining a vast new audience.

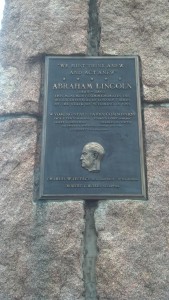

Adjacent to the Lincoln monument is a marker dedicated to Packard Motor Company president Henry B. Joy, the first president of the Lincoln Highway Association.

The road up to this point from Cheyenne, which sits at roughly 6,000 feet, travels across the high plains. This is what Colorado’s Front Range must have looked like before suburbia. The landscape here is certainly majestic and my photos don’t do the topography justice. It’s broad. It’s easy for the eyes to gaze out over the vast expanse.