California Hill, near modern-day Brule, Neb., is where many westward settlers encountered their first large climb from the Platte River valley to higher terrain. (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

BRULE, Neb. — It may not look like much, but the beautifully rolling topography wedged between the Platte River’s north and south forks was one of the first big endurance tests for any westward-bound emigrant.

This is California Hill, the place where thousands of wagons carrying settlers and supplies bound for California, Oregon and other points westward encountered their first major uphill climb. There certainly aren’t any major mountains here, but as central Nebraska pushes into western Nebraska, a gradual change in topography is noticeable. In this case, a big hill is still a big hill, especially when the previous few hundred miles have been absolutely flat.

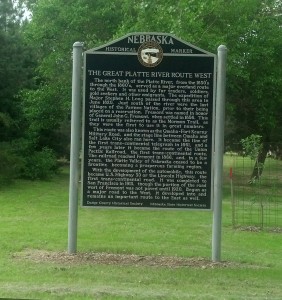

Most westward emigrants heading through Nebraska would stick to the south side of the Platte River. (Many Mormons traveled along the north side of the river.) Near modern-day North Platte, the city that’s home to the Buffalo Bill Ranch, the river forks into two branches: The South Platte continues to the southwest into northeastern Colorado and onward to Denver while the North Platte continues in a northwesterly direction toward east-central Wyoming and, eventually, South Pass, the all-important crossing of the Rocky Mountains.

At California Crossing, emigrants would ford the South Platte, trudge up California Hill toward the north and northwest and later connect with the North Platte. This territory is apparently full of old emigrant wagon ruts.

I was on the lookout for these remainders from the former overland trails, but couldn’t pinpoint any within view of the dirt road I drove up from U.S. 30 to reach this beautiful and peaceful windblown spot.

Post continues below …

For his 2001 book Wither Thou Goest, author Patrick Simpson visited California Hill as part of his journey following his ancestors’ 1878 trek westward. He had some trouble at California Hill, just like me: