KEARNEY, Neb. — When the Lincoln Highway was routed through this city near the southern bend of the Platte River, a local farmer put up a sign trumpeting the fact that Kearney was 1,733 miles to Boston and 1,733 miles to “Frisco.” While the Lincoln Highway doesn’t go to Boston, that didn’t matter: Kearney was the “Midway City.”

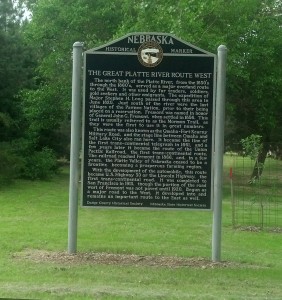

It’s in the middle of somewhere, for sure. The U.S. Army established a rudimentary fort here in 1848 to help protect westward settlers passing through the Platte River valley. Fort Kearny (note the difference in spelling, the result of an error on an official application) was ideally situated because various trails from the east converged here to follow the Platte westward. The future transcontinental railroad would come through town, too.

Driving along Central Avenue, the broad brick-lined main commercial street, it’s hard to not to get the feeling that back in the day, Kearney had big dreams of being a major metropolis. The streets are wide — almost too wide — and the grid is quite extensive compared to most Platte River Valley towns along the Union Pacific Railroad and Lincoln Highway. Overall, there’s a slight emptiness to the city’s expansive scale.

In its first few decades, Kearney quickly grew into a boom town.