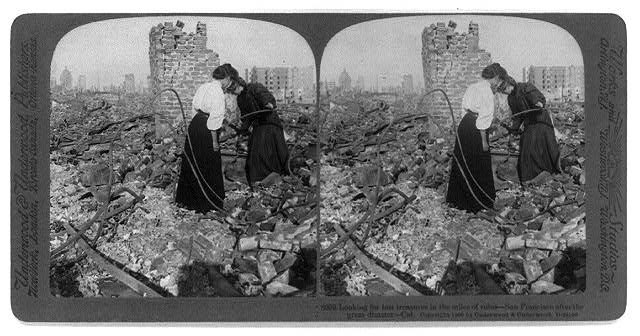

Racing toward dusk through northern Nevada on Amtrak’s California Zephyr (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

WASHINGTON — When I set out on my Lincoln Highway adventure in early June, my goal was to write a travelogue in real time or as close to real time as possible. Well, for those who have been following my dispatches on this blog or via social media, you know that my good intentions to do that ran into the realities of having to drive long distances, exhaustion, limited Internet access at times and other factors that slowed me down. Then a backlog of posts started to build. Then the reality of normal life back in D.C. came into play. You get the idea …

Although I’ve been slowly digging out of the backlog and I have now posted a dispatch featuring the last leg of my westward trip on the Lincoln Highway to San Francisco, I’m not done with the Lincoln Highway Guide just yet. There’s still more writing from my adventures I’m sorting through. I have plenty of notes to make sense of.

Since leaving San Francisco on June 24, I’ve actually continued traveling along portions of the highway and I expect that I will continue to, albeit gradually, write about the various places along the way, though it probably won’t be in sequential order.

So here’s a preview of where I’ve been and what I’ve done since finishing the main part of my Lincoln Highway adventures:

- I took Amtrak’s California Zephyr from Emeryville, Calif., to Denver, and later from Denver to Chicago. Its route follows, in part, the route of the first transcontinental railroad, a rail link championed by Lincoln while in office and completed four years after his assassination.

- In Chicago, which sits on an auxiliary route of the Lincoln Highway, I visited various Frank Lloyd Wright sites, including the playroom where the inventor of Lincoln Logs spent much of his childhood. I also visited Lincoln Park and Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ statue of Abraham Lincoln.

- In Washington, D.C., I’ve revisited some Lincoln-related sites, including the Lincoln Gallery in the Smithsonian American Art Museum, where Lincoln’s second Inaugural Ball was held on March 6, 1865.

- I’ve driven the bulk of the Lincoln Highway in western Pennsylvania two more times (including a lazy afternoon at historic Ligonier Beach) and the majority of the highway in Ohio a second time, including a stop at the Hungarian pastry shop in Wooster (which may be my new favorite place for food in the Buckeye State).

- I’ve driven the majority of the Lincoln Highway in New Jersey, including stops in Princeton and Newark for Portuguese food.

- I’ve visited a few sites related to Horace Greeley in New York City. The sites aren’t directly tied to the Lincoln Highway, but to understand the life and times of Abraham Lincoln, you must understand the life and times of Horace Greeley.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ statue of Abraham Lincoln in Chicago’s Lincoln Park (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

So, please check back for more updates of my adventures.