KEARNEY, Neb. — After a few days of on-the-road food, I was desperate for something different — and hopefully healthier. Along the way, I’ve been doing my best with dried fruit, mixed nuts and water in an effort to try not turn into a roadtrip pig. But I’ve had my fair share of fast food, too.

By the time I arrived in Kearney, I was exhausted. The drive from Cedar Rapids, Iowa, with all of my stops, took me longer than I had planned for. I was thinking about checking out one of the downtown brewpubs, either Cunningham’s Journal or Thunderhead Brewing Company, but I wasn’t up for beer and when I drove by, they were packed.

Yelp pointed me to Hunan Chinese, which reviewers had indicated was “[h]onestly, probably the best Chinese in a 100 mile radius” and when considering all of the local restaurant offerings is “[a]s good as it gets for Kearney.” It wasn’t downtown but it was close to my hotel. And some Chinese food sounded good at the moment.

I have a soft spot for Chinese restaurants in the United States. I used to work at a fairly Spartan-looking Chinese take-out operation in high school. Over many generations, Chinese restaurants in the United States have become a critically important part of the American culinary footprint. The first Chinese restaurants in the U.S. opened during the California Gold Rush in mining towns — “Caucasian miners feared, ridiculed and discriminated against the Chinese, but loved their food,” according to the Sacramento Bee — but overtime, spread east, to places just like Kearney.

“What began in this country as exotic has become thoroughly American,” The New York Times wrote in 2004.

Recently, I’ve been seeking out more and more traditional Chinese cooking on my travels and when I can Sichuan food in particular. This has included some knock-out dishes at Han Dynasty in Philadelphia and great meals in Penang, Malaysia, where Chinese merchants brought their cooking traditions to the British outpost at George Town. I also recently ventured to Fredericksburg, Va., about an hour from Washington, D.C., to sample the cooking of acclaimed former Chinese Embassy chef Peter Chang. The chef has a bit of a cult following and has a somewhat mysterious track record of disappearing and reappearing in a random city with a new restaurant located in a seemingly nondescript strip mall. Chang has bigger plans for bringing his food to larger audiences.

Perhaps, Chang’s cooking will appear here in Kearney someday. In the meantime at Hunan Chinese, I knew I would likely be getting standard Americanized Chinese favorites, but that was OK. My stomach wanted some crab rangoon.

I pulled up to the Regency Plaza strip mall on W. 11th Street at Third Avenue, and there it was. Hunan Chinese was fronted with some solid-looking brownish-gray concrete blocks punctuated by regular intervals of vertical abutments. The restaurant was windowless. It looked like a solidly built bunker. This is probably where I would go first in the event of a tornado but not necessarily for a good meal. But strip-mall dining can be surprisingly awesome, too, when you find the right place.

Good urban design these days dictate that windowless exterior walls deaden street life. In this case, Regency Plaza is just a simple strip mall with a modest parking lot in front. There’s not much street life to ruin. I am generally hesitant about walking into an establishment where it’s hard to see inside, or at least catch a glimpse of what’s immediately beyond the vestibule. In this case, I just had to walk on in to see what awaited me.

My eyes had to adjust from the relatively-cloudy-but-still-bright light from outside to the interior of the restaurant, which is very dim. I quickly scanned the place from left to right. There was a giant double buffet, flanked by by deep six-person booths.

There were bright lights coming from the kitchen through a set of doors. Then at right, there’s a fully-stocked bar adorned with some chintzy decorations. The bar had a few stools and the cash register. This was also, presumably, the place to pick up phoned-in orders, since it’s the first thing customers encounter coming in from the vestibule. (There’s no evidence of online ordering available.)

An Asian woman — I assume she was Chinese — greeted me: “Hello. Take out?”

“No, table for one,” I replied. “Thank you.”

I was ushered over to a dark booth over by the buffet spreads, which were dark and empty of food. (The restaurant uses them for lunch and an all-day buffet on Mother’s Day and Valentine’s Day.) I sank into the booth which was made with a Naugahyde-type of material. My booth had certainly seen some use over the years.

After giving me about two minutes, my server came back for my order. Like many Chinese restaurants, Hunan Chinese suffers from having too many dishes available. I quickly picked a relatively bland-sounding, non-fried entree — sliced pork with mixed vegetables — to go with my hot and sour soup and crab rangoon.

There was just one family in the restaurant for dinner and they were slowly wrapping up their meal.

“That wasn’t too spicy,” an older woman in that party said. When my hot and sour soup arrived, there was barely any bite to it. Any reputable hot and soup should have a good balance of pepper and vinegar. Mine was enjoyable but for the most part bland. I imagine that the restaurant is catering to the woman at the other table and not me.

As I was munching on crab rangoon — which were delightfully crispy and not too greasy and chewy — I was paging through “Fremont’s First Impressions: The Original Report of His Exploring Expeditions of 1842-1844” to see what was awaiting me farther west along the Lincoln Highway and Great Platte River Road.

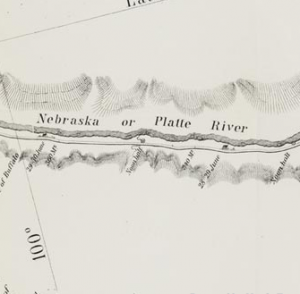

Part of a map of the Platte River Valley made by Charles Preuss (Denver Public Library >>)

From the journal of the expedition cartographer, Charles Preuss, who was separated for a few hours from the rest of the expedition somewhere near modern-day North Platte, Neb, about 100 miles up the road:

After remaining here two hours, my companion became impatient, mounted his horse again; so I lay still. I knew they could not come any other way, and then my companions, one of the best men in the company, would not abandon me. The sun went down, he did not come. Uneasy I did not feel, but very hungry; I had no provisions but could start a fire; and I espied two doves in a tree, I tried to kill one; but it needs a better marksman than myself to kill a little bird with a rifle. I made a large fire, however, lighted my pipe–this true friend of mine in every emergency–lay down, and let my thoughts wander to the far east. It was not many minutes after when I heard the tramp of a horse, and my faithful companion was by my side. … To the good supper which he brought with him I did ample justice. He had forgotten salt, and I tried the soldier’s substitute in time of war, and used gunpowder; but it answered badly–bitter enough, but no flavor of the kitchen salt.

Fortunately for me, my Chinese food didn’t need any salt. And I’m glad I didn’t need to restort to using gunpowder as seasoning like Charles Preuss did back in the 1840s. (Hunan Chinese also doesn’t use any MSG, according to its website.)

For Americanized Chinese food, Hunan Chinese did a pretty good job. It was better than expected.

What food will await me as continue into the Rocky Mountains? I’ll have to guess for the time being. I still have to the cross the High Plains.

My wife is Chinese and grew up in Reno, NV. She tells some fine stories about her father’s fruitless search for “real” Chinese food in the west. Bottom line, stick to California.

Did you ask the waitress how she ended up in Keanrey? I’ll bet it’s an interesting story.

Carry on!