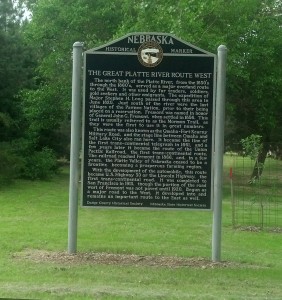

The Great Platte River Road carried countless westward settlers across the Great Plains and into the Rocky Mountains. (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

FREMONT, Neb. — Of the most important waterways in the United States, the Platte River usually doesn’t rise to the top. Unlike the Mississippi and Missouri, it’s extremely shallow.

Washington Irving called the Platte “the most magnificent and useless of rivers.” But the Platte, called “Nebraska” by Native Americans, helped change the shape of American history. This route allows a relatively easy path into the interior.

The Great Platte River Road was used by countless settlers heading west to Oregon, California and Utah. The Union Pacific Railroad’s Overland Route follows the Platte westward along what was the nation’s first transcontinental rail link.

With a level route into the interior, it made sense to have the Lincoln Highway follow the Platte west as well. From Iowa, the original alignment of the highway takes the road into Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Omaha, Neb. But U.S. 30 makes a beeline from from Iowa’s Loess Hills to Fremont via Blair, Neb. Since I was continuing onto Kearney that day, I opted for the more-direct route.

Crossing the Missouri River adjacent to the Fort Calhoun nuclear power station — which was sidelined in 2011 after severe flooding along the Missouri River — U.S. 30 climbs from the valley to higher terrain on its way to Fremont.

This city sits along the Platte, which for much of its path west, is wide, shallow and broken into myriad small channels within its banks, depending on the how much water is present, which usually isn’t that much.

The Mormon Trail passed through this area to follow the route west on the north bank of the river. Other settlers crossed at Fremont to stay on the Platte’s south bank.

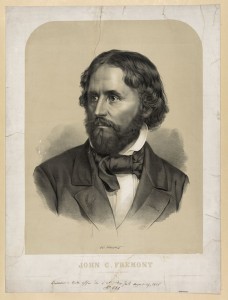

John C. Frémont (Library of Congress Prints and Photograph Collection >>)

This might be a good place to introduce John Frémont, the legendary Pathfinder, for whom this town was named for in 1856. Frémont was a latter-day Lewis and Clark and was joined by others, including Kit Carson, during a handful of westward expeditions in the 1840s.

While these journeys didn’t necessarily discover new routes west, the reports made from his expeditions, which included detailed mapping by Charles Preuss, were used extensively by settlers as a guidebook.

According to the National Archives:

Frémont’s report provided practical information about the geology, botany, and climate of the West that guided future emigrants along the Oregon Trail; it shattered the misconception of the West as the Great American Desert.

Frémont became famous for his western adventures, which also includes the Pathfinder being courtmartialed for insubordination involving the governance of California after the Golden State’s annexation by the United States.

But Fremont remained popular. He later represented California in the U.S. Senate where he was known for being an abolitionist and in 1856 became the Republican Party’s first-ever presidential candidate. Fremont lost to Democrat James Buchanan — who lived in Lancaster, Pa., a city I passed through earlier in my trip.

But the Pathfinder was better at exploring the West than he was a politician or businessman. Fremont made millions but ran into trouble with railroad investments after the Civil War.

And it’s along the Platte River where Fremont began his trek west. (He technically linked up with the Platte at present-day Kearney.)

I’m headed that way, too, with the accounts of his expeditions at my side:

From its mouth to the junction of its main forks the valley of the Platte generally about four miles broad is rich and well timbered, covered with luxuriant grasses. The large purple Aster was here, the characteristic, flourishing in great magnificence.

Where Frémont saw large purple flowers, I’m seeing giant grain elevators. But more on that later …

Pingback: No, I Didn’t Use Gunpowder to Season My Chinese Food | The Lincoln Highway Guide

Pingback: A Quick Fast Forward to the Western Terminus | The Lincoln Highway Guide

Pingback: ‘Living the Legend’ in Cheyenne | The Lincoln Highway Guide

Pingback: ‘Give Me Solitude’ Among the Ancient ‘Grotesque’ Trees | The Lincoln Highway Guide