Pittsburgh’s Point Bridge, seen here around 1900, was the first of three bridges to span the Monongahela River right before it meets the Allegheny River to form the Ohio River. (Photo by the Detroit Publishing Co. via the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

PITTSBURGH — When Fort Duquesne was situated at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers by the French, this area was obviously strategic. It protected the gateway to the Ohio Valley and was fought over during the French and Indian War. But as cities go, the spot where modern Pittsburgh would eventually take shape wasn’t necessarily an easy place for future growth.

Most cities thrive on level ground, something that is a scarce commodity here. Constrained by its rivers and hemmed in by mountains, Pittsburgh had no such level-ground luxury.

San Francisco faced similar issues with its hilly terrain, but instead of growing organically with its setting, its street grid system brazenly defied it, creating the often steep streets that have become one of San Francisco’s signature urban elements.

While San Francisco conquered its topography with a uniform street plan, Pittsburgh conquered its difficult terrain with its infrastructure, allowing the city to expand into its higher elevations, across its rivers and other areas where the terrain would normally limit any ordinary city.

Pittsburgh functions because of its bridges. They’re everywhere.

Bridges over rivers, bridges over ravines, bridges over other bridges and the complex web of roadways and viaducts that connect them all. This city could not exist without them.

So for someone who is fascinated by urban infrastructure, Pittsburgh is a place that has always drawn me in. It’s a challenge to drive here and certainly intimidating to an outsider. You have to know where you’re going because one missed turn might lead you to a road that could take you across a river or down a mountain without an easy way to doubleback. You may think I’m crazy, but I love driving in Pittsburgh.

When I was the navigator on family roadtrips between Michigan and Washington, D.C., I would sometimes tell my parents to take a detour off the Pennsylvania Turnpike through Pittsburgh via the Penn-Lincoln Parkway (today part of Interstate 376) and the Fort Pitt Tunnel and Bridge. Going this route offers one of the most dramatic entries to a city anywhere in North America, where after you emerge from the Fort Pitt Tunnel, you’re suddenly on a bridge over the Monongahela River with the city’s cluster of downtown skyscrapers in full view.

Post continues below …

The George Westinghouse Bridge carries U.S. 30 over the Turtle Creek Valley in the borough of East Pittsburgh, Pa. (Photo by Joseph Eliott via the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington)

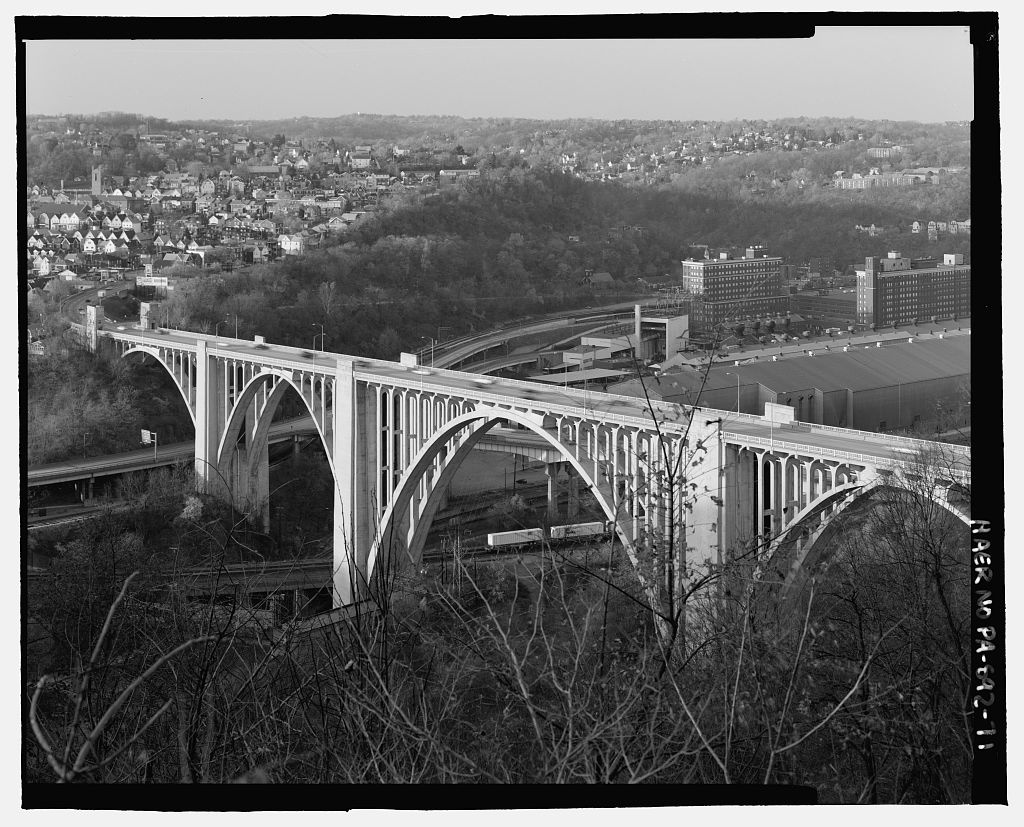

There are many great bridges in Pittsburgh worthy of more in-depth discussion, but the one that’s important to the Lincoln Highway is the George Westinghouse Bridge, southeast of the city in the borough of East Pittsburgh.

The original route of the highway coming from the east had to confront crossing the Turtle Creek Valley. According to the Lincoln Highway Association’s official map, the route had a difficult descent into the valley before having to head back up on the other side.

The Turtle Creek Valley was considered one of the worst bottlenecks anywhere on the highway in its early history. It took this bridge, which broke engineering records when completed in 1931, to solve the problem. The open-spandrel concrete arch bridge, with five spans, is 1,598 feet in total length.

But like other bridges, you don’t get to take in the full grandeur of the bridge by simply crossing it. As PGHBridges.com describes it:

The majesty of the bridge structure is lost to those who merely cross its deck, although the presentation of impressive views of the valley’s industrial heritage and the westward traveller’s first glimpse of the building tops of downtown Pittsburgh make it difficult not to stray one’s gaze laterally.

To truly appreciate this bridge, it may make sense to take the old route into the valley to gaze up at it.

- (Photo by Joseph Eliott via the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

- (Photo via the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

- (Photo via the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

- (Photo via the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

- (Photo via the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

- (Photo via the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)