Damage from Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. (Photo by Flickr user EditorB via CC BY 2.0 >>)

BERKELEY, Calif. — Back in 2005, a friend of mine was contemplating a trip to New Orleans.

“You should go to New Orleans before a huge hurricane destroys the city,” I said.

I had been recently reading about the nightmare Hurricane Pam scenario that disaster planners had been predicting for the city.

My friend ended up going to the Big Easy and had a good time. But later that year, Hurricane Katrina brought its destruction to New Orleans, bringing a terrible level of devastation and disruption and depopulation few major American cities have ever had to face.

When I eventually make it to New Orleans — who knows, maybe later this year? — I know I will never experience what made the pre-Katrina city such a special place.

Great cities change and evolve of course. They rebuild after great disasters like hurricanes, earthquakes and fires. Usually, they triumph over their struggle and emerge stronger, better places. San Francisco, my final Lincoln Highway destination, awaiting me across the bay from Berkeley, is a testament to that.

Post continues below …

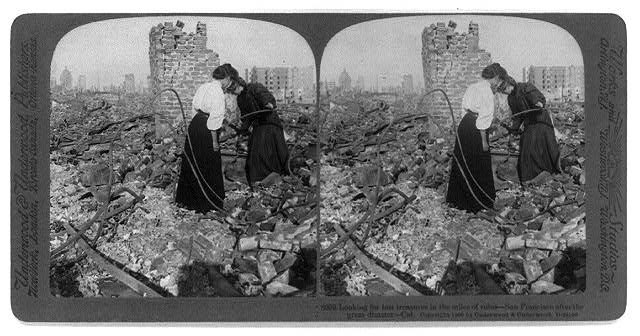

Two woman search the ruins of San Francisco in the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake and fire. (Photo via Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division >>)

New Orleans, of course, is more precarious. It’s living on borrowed time. Rising sea levels, sinking land and stronger storms are likely to swamp the city again someday, no matter how high levees can be made.

Heading into the Bay Area, on the final leg of my crosscountry Lincoln Highway trek, disaster has been on my mind. I blame this in part to my first job out of college, working as a consultant for a Federal Transit Administration disaster and emergency preparedness program that aimed to help local transit agencies coordinate with federal, state and local government and first responders before disaster struck. (My last trip to the Bay Area was during a work trip for the FTA in 2002.)

Natural disasters and California are closely intertwined, as residents of the Golden State know well.

Although I’m not paranoid about looming disasters when visiting places like California, I’m often thinking about them. Driving around Southern California, I sometimes breathe a sigh of relief in stop-and-go traffic when I clear a freeway flyover ramp, presumably built to strong seismic standards but nevertheless potential killers in a strong quake.

Here in Northern California, earthquakes have been on my mind, too, and help guided my choice in hotels.

Destruction in San Francisco’s Marina District following the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake (U.S. Geological Survey photo by Flickr user CIROnline via CC BY 2.0 >>)

Besides free parking and accessibility to a BART station and Amtrak — the California Zephyr will take me back east — I wanted to stay in a hotel that would be less prone to liquefaction should a major earthquake strike the Bay Area during my stay.

Hotels, of course, don’t detail their seismic risk on their booking pages, but it was clear that the Doubletree at the Berkeley Marina, where the Lincoln Highway connected with the ferry to San Francisco before the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge was constructed, was built on reclaimed land on the edge of the bay. Reclaimed land is more vulnerable to liquefaction.

I instead picked a Holiday Inn Express a mile or so away from the bay on University Avenue steps from an old Lincoln Highway alignment. Seemingly, that was on more stable soil. But how was I really to know the reality of the seismic risks? I’m likely just being overly cautious.

Californians have been hardened by disasters over the years. Many live in the Golden State knowing the risks or are blissfully oblivious to them.

While earthquakes and wildfires might be the most prevalent risks, the biggest disaster California faces may be weather related.

Post continues below …

Sacramento could be the next New Orleans. California’s capital city is low lying at the confluence of the Sacramento and American rivers and is protected by levees. Its Katrina could come in the form of an “atmospheric river.”

This weather phenomenon, which targets a powerful funnel of Pacific precipitation at California, can send a succession of powerful rainmakers into the Golden State. It can rain for weeks.

In the winter of 1861-62, an atmospheric river devastated the state, turning much of the Central Valley into an inland sea. In Sacramento, the newly elected governor, Leland Stanford, had to take a rowboat to the Capitol in January 1862. The city was flooded for three months. The state government temporarily relocated to San Francisco. The state later went bankrupt.

Following the flooding, some streets in Sacramento were raised anywhere from 9 feet to 14 feet. Today, Sacramento and the Central Valley have a complex network of levees and flood-protection infrastructure to help keep rivers from inundating farmland and populated areas.

According to the Weather Underground’s analysis of California’s Superstorm, a repeat of the 1862 flooding is not a question of if, but when.

The USGS suggests that up to 120” of rain might fall in California over the course of such an event (in favored orographic locations) the run-off from which would flood the entire Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys as well as the basins of Southern California. A very detailed analysis from the report predicts damage to exceed $300 billion with up to 225,000 people permanently displaced (in terms of complete destruction of dwellings) and a further 1.2 million forced into evacuation.

Driving along State Route 99, one of the major north-south freeway arteries in the Central Valley, I was trying to envision the semi-rural, semi-suburban landscape being totally inundated. Someday, it will be inundated in what could prove to be the most significant natural disaster ever in California.

If flood protections fail here after the next big inundation, will California refortify its defenses like in New Orleans? Will it be worth it?

Post continues below …

In one sense, I’ve felt somewhat fatalistic with my travels this year. In Bangkok, I was fascinated with all the elevated infrastructure in the Thai capital, which is situated on low-lying land that is gradually sinking. Climate change poses a huge risk to Bangkok, just like it does in New Orleans and so many other cities around the world. I was also amazed that Bangkok managed to build an underground Metro line in such a watery environment. Cities adapt.

Post continues below …

The Montague Street tube underneath the East River, after it was pumped out after Superstorm Sandy. (Photo by Marc A. Hermann/MTA New York City Transit via CC BY 2.0 >>)

As I was getting out of New York City in advance of Superstorm Sandy last year, I made a point of taking the R train through the Montague tube under the East River and Lower Manhattan, having a uncomfortable feeling that it would surely flood in the storm surge anticipated.

Sure enough, Lower Manhattan — and so many other places in and around New York City — faced record-breaking storm surge. The Montague Street Tunnel was submerged for weeks after the storm. (It’s now in the midst of a 14-month rehabilitation to rebuild systems damaged by seawater.)

Superstorm Sandy demonstrated just how vulnerable our cities are.

I feel like I should go to Key West and Miami Beach before they’re destroyed by hurricanes. Same with New Orleans. I feel like I should get to Tokyo and Istanbul before giant earthquakes strike. The list goes on.

Life is short and for most of my life, I’ve been mostly stuck in a triangle bounded by Michigan, New York City and Washington, D.C. I’ve yearned to break out. This year, I’ve broadened my horizons with trips to the Caribbean, Hawaii and Southeast Asia. Then, I embarked on my cross-continental trip. And I’m nearly done with the westward journey.

***

Here in Berkeley, the University of California has been used as a backdrop for multiple earthquake documentaries and television programs because the Hayward Fault cuts through campus. In fact, Memorial Stadium sits atop the fault.

Despite the seismic risk, UC-Berkeley has been slow to retrofit buildings which have been classified as vulnerable to earthquake damage.

I didn’t get to see Memorial Stadium, but I did see the landmark Campanile, known formally as Sather Tower. The 307-foot structure is the third-tallest clock and bell tower in the world.

It’s tall. It’s slender. In a seismic sense, it seems extremely vulnerable.

From a transcript of a 2005 National Public Radio report by John McChesney on the risks the San Francisco area faces in the next big quake, which could come on the Hayward Fault, not the more noteworthy San Andreas Fault:

McCHESNEY: We’re standing in the historic epicenter of the UC, Berkeley campus with spokeswoman Christine Shaff. The most notable structure here is the 30-story campanile, a Bay area icon.

Ms. CHRISTINE SHAFF (University of California Spokeswoman): The Hayward fault is a few hundred yards to the east of where we’re standing. It’s a steel frame structure built to the safety standards of its time. It’s also not occupied on a constant basis.

McCHESNEY: But if it came down…

Ms. SHAFF: That would be very sad.

McCHESNEY: Sad, indeed, to anyone unlucky enough to be walking by on this crowded campus. The last quake on the Hayward was in 1868, so the fault is now cocked to deliver a temblor in the neighborhood of magnitude 7. The results, everyone agrees, will be horrific.

Horrific is right. I’m glad I’ve been able to see it before the next large earthquake strikes.

Despite these dangers and impending doom, life goes on in Berkeley and in California as a whole. The one thing to keep in mind when fretting about the risk of disaster is to appreciate how beautiful the landscape it because of it.

On my way into Berkeley from Stockton, I had to cross the Diablo Range at Altamont Pass on Interstate 580. I wasn’t prepared for just how beautiful it was. The Hayward Fault cuts through here too, and helped form this stunning landscape.

This is part of why Californians choose to live in such a naturally hazardous place.

Altamont Pass crossing the Diablo Range from the Central Valley into the Bay Area (Photo by Flickr user John Loo via CC BY 2.0 >>)