A historic Lincoln Highway marker stands alongside the Loneliest Road in America. (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

FALLON, Nev. — In my trek westward toward San Francisco on the Lincoln Highway, my earlier travels across the grand emptiness of the Great Plains may have spoiled the so-called “Loneliest Road in America.”

Along U.S. 50, the so-called “Lonliest Road in America,” near Austin, Nev. (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

Sure, the distances between towns on U.S. 50 in Nevada can be quite far, but I was never truly alone out in the middle of nowhere like I had been, for instance, for most of U.S. 30 near the Medicine Bow Mountains in Wyoming, a stunningly beautiful place that made me feel blissfully alone under the endless mountain-framed skies.

On the Loneliest Road in America — that description for this stretch of U.S. 50 came from a 1980s Life magazine feature and is now used for regional marketing — I encountered a car or truck every few miles — sometimes even more often than that. At historic markers and other points of interest, there had been other tourists, including those seeking to get souvenir Loneliest Road travel passports stamped along the way.

When it comes to central Nevada, Lincoln Highway enthusiasts often talk about the older, more desolate alignments that roughly parallel and intersect the modern road along the way. Those who are more adventuresome might want to attempt those rougher alternative routes less traveled. While those roads may be more historically accurate, adhering to the original 1913 Proclamation Route, I didn’t want to test the limits of my rental car out in the desert.

The vastness out here hasn’t made such as big an impression as I thought it would. Yes, this territory has a rough beauty, but it’s not stunningly beautifully. But that’s not why I came out all this way.

I wanted to feel true isolation that I thought was going to be out along the Loneliest Road in America. I had wanderlust and wanted the road to myself. I wanted to drive into dusty settlements with tumbleweed blowing aimlessly across the road as I had envisioned. Sure, there’s plenty of dust and sagebrush along U.S. 50, but I guess one too many John Wayne movies painted a more remote, hardscrabble landscape. (Eureka, however, came close to looking like a Hollywood backlot.)

Post continues below …

The Loneliest Road in America, U.S. 50 in Central Nevada. (Photo by Flickr user Bruce Fingerhood via CC BY 2.0 >>)

The distances haven’t seemed as daunting as I thought they would be. An hour-long drive between Loneliest Road settlements turned out to be not all that intimidating as the large gaps between named place-name town labels seemed to indicate when I was a child closely studying the Rand McNally road atlas.

The weather conditions for my trip across Nevada were near perfect. Not terribly hot with big friendly-looking clouds dotting the sky. If I’d be inching along this not-so-seemingly-endless road during a snowstorm, I’d certainly have a different story to tell.

But it was essentially more of the same. I imagine that if I would have started my cross-country trek in San Francisco and went east toward New York City, encountering this territory for the first time would be an amazing sight and places farther to the east, like western Iowa or the high plains of Nebraska, wouldn’t have the same kind of impressionable impact as they did. In the American West, the full impact of a monumental landscape is all a matter of perspective and progression.

The Great Basin is an empty place. Parts of it look like a moonscape. It can be very desolate. As I took it it all in, I could better visualize details from many of the historic journeys crossing the American West.

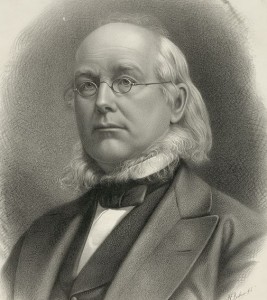

In one dispatch from his famous 1859 overland crossing to San Francisco, New York Tribune publisher Horace Greeley detailed a lonely mail-carrying substation along the Central Overland Route between Salt Lake City and Nevada’s Carson Valley. It might send shivers up the spine of anyone who obsessively checks their smartphone:

The station keeper here lives entirely alone — that is when the Indians will let him — seeing a friendly face but twice a week, when the mail stage passes one way or the other.

Horace Greeley (Photo via Library of Congress Photographs and Prints Division >>)

He deeply regretted his lack of books and newspapers; we could only give him one of the latter. Why do not men who contract to run mails through such desolate regions comprehend that their own interest, if no nobler consideration, should impel them to supply their stations with good reading matter! I am quite sure that one hundred dollars spent by Major Chorpening in supplying two or three good journals to each station on his route, and in providing for their interchange from station to station, would save him more than one thousand dollars in keeping good men in his service, and in imbuing them with contentment and gratitude.

I would feel very lonely in such a situation. I’d also probably go nuts if I didn’t have something to read or something productive to occupy my time. I suspect most people would feel the same.

But yet people have come out to the Great Basin over generations for one reason or another. On the surface, coming out here seems foolish. Greeley declared in one overland dispatch that “[i]f Uncle Sam should ever sell that tract for one cent per acre, he will swindle the purchaser outrageously.” He also complained about how the water out this way was “about the most detestable” he had ever consumed. “I mainly chose to suffer thirst rather than drink it.”

Yet, there was money to be made out in this wasteland along the road to the promised land of prosperity in California. And people came. The ghosts towns like Ward or the barely settled places like Eureka stand today as testaments to the boom days. But I suspect there are plenty of other people who aren’t necessarily out here because their economic livelihood depends on it. They actively seek the physical isolation, something that isn’t in short supply out here.

In American Road, Pete Davies noted that Orr’s Ranch in Utah, out in the middle of nowhere along one of the desolate stretches of the Lincoln Highway, “had been settled in 1898 by a Scot named Matthew Orr ‘who found it difficult to live at peace with his neighbors’ and went to a place where he wouldn’t have any.”

Some people who just want to be left alone, so they seek refuge off the beaten path. I encountered that on a 2011 roadtrip in Colorado when I came across a house surrounded by a high spiked stockade fence about 10 miles outside Fairplay along U.S. 285. Its yellow “Don’t Tread on Me” flag sent a message that the fortified homestead wouldn’t be the best place to stop to ask for directions. (Not that I needed any.) The people inside the stockade clearly didn’t want to be disturbed and they didn’t want passing travelers violate their property rights.

I don’t think I would last long holed away in such an environment, actively keeping the outside world out. I think I’d become paranoid. I might like to spend time away from the madness of the world, but shutting it out completely would drive me crazy, especially way out in the desert with limited resources. (I’d likely develop an irrational fear of being gobbled up by some sort of scary Tremors-like desert worm creature.)

Michel de De Montaigne wrote in On Solitude that “it is not enough to withdraw from the mob, not enough to go to another place: we have to withdraw from such attributes of that mob as are within us. It is our own self we have to isolate and take back into possession.”

When you head into the desert to seek solitude and desolation, you’re supposed to emerge renewed, refreshed and refreshed — ready to face whatever you need to face. With the Sierra Nevada mountains a few hours ahead of me — and beyond them, crowded California — I wasn’t sure what I was driving toward to face, except my inevitable return journey east once I reached the end of the Lincoln Highway in San Francisco.

Still, as I continued west, I felt there was still some unfinished business for me out in experiencing the emptiness of the Great Basin. I was ready to head home, eventually. But as I was rapidly running out of lonesome road and wasn’t quite ready to reenter civilization.

***

Post continues below …

On the way to Fallon, the tiny town of Austin pops up suddenly at the bottom of a twisty descent down from the nearly 7,000-plus foot Scotts Summit mountain pass. Today, barely 200 people live in this former mining boom town. Ten-thousand people crowded into Austin in the 1860s. But the prosperity waned heading into the 1880s when riches were found elsewhere.

I was on a quest to have lunch in this small barely-a-place place since I skipped the chance to eat back in the previous barely-a-place place.

The International Cafe and Bar in Austin, Nev., as seen in 2005. It’s since gotten a new paint job.(Photo by Flickr user Irish Typepad via CC BY-SA 2.0 >>)

Doing a little bit of guidebook and online research, I settled on the International Cafe and Bar, which sits inside an aging two-story wooden building with a covered front boardwalk decorated with wagon wheels and other rustic items from days gone by.

According to Brian Butko’s Lincoln Highway Companion guide, this building was originally in Virginia City but was moved to Austin in the 1860s. The International Cafe and Bar is, according to Butko’s guide, “not unlike what it would have been in the Lincoln Highway era when it was quite the going business.”

Scanning TripAdvisor reviews, this place looked like a great place to chat up the locals, though Butko’s guidebook warned about making jokes about cowboys at night. One TripAdvisor user said the staff was “polite but reserved.” Another described a fairly Spartan, no-nonsense place:

The inside … was spotless clean, fresh with no cooking smells, and greeted right away, even though she appeared to have had a very long and hard night.

I didn’t really have too many other options for lunch in Austin and I had already exhausted my stash of road-trip beef jerky. When I walked into the International Cafe and Bar, I found the wood-paneled interior to be mostly deserted. A family was seated at a table on the other side of the room waiting to order. They were talking quietly. Near the doorway to the kitchen, there was a woman whose head was mostly covered by a yellow scarf draped over her head and shoulders. She moved quietly attending to tasks between the front and back of the house.

As she approached the plain-and-simple-looking bar, where I had taken a seat, her face came into more detailed focus. She looked like a strange fusion of Sissy Spacek from Carrie and the Log Lady from Twin Peaks, only partially shrouded in bright yellow. She looked like she knew all of the town’s secrets.

I said “Hi” but she was silent as she briefly exchanged eye contact with and dropped a menu on the counter in front of me and turned her back to deal with something on an adjacent counter. She didn’t seem like she was big into chit-chat.

When my waitress returned in a couple minutes, she quickly took my order and quietly went back to the kitchen, which was located far to the back of the building. I think I ordered a chicken sandwich with fries. But I can’t remember. If there was anything that stood out on the menu, I would have ordered it and it would have made some sort of impression, good or bad. I should have just ordered a burger. It would have been overly greasy but at least it would have been memorable.

I came into the International Cafe and Bar thinking that this was going to be some kind of signature experience from being out in the middle of nowhere along the Lincoln Highway. But sometimes what you hope to experience doesn’t play out as imagined.

This place was very silent, except for the bits and pieces of the occasional conversation I could hear from the other table across the room. The little I heard wasn’t very interesting.

“How many hours do you think to Great Basin National Park?” the woman seated at the table asked the man I assumed to be her husband. The kids with them were for the most part quiet and well behaved with occasional fidgeting. They seemed to be bored. But then again, everything about this place, from the waitress to the company to the overly plain and average interior was yawn-worthy that afternoon.

Maybe I should have booked a room in Austin and hung out at the bar at night to make cowboy jokes in front of the locals. Now that wouldn’t have been yawn-worthy. But I wanted to get out of this yawn-worthy landscape in central Nevada. I guess it was a sign that being out in the middle of nowhere was becoming more and more tiresome. Luckily, something different wasn’t too far away.

***

It’s about 110 miles from Austin to Fallon, a town that is a little over an hour to the east of Reno and Carson City, my destination for the night. Fallon marks a point of gradual reintroduction to civilization. There seemed to be be more cars the closer I got to Fallon.

I had the Stone Roses playing and was getting toward the end of the British band’s eponymous 1989 album. “This Is the One” is one of those songs where listeners aren’t quite told what the exactly is “the one she’s waiting for.” But the meaning of the words don’t matter much. The music soars. It’s energetic. It’s great driving music, where the ups and downs of navigating the road often seem to deliberately hit strategic points in the lyrics or instrumentation.

For me, “This Is the One” ended right around a turnoff to the Grimes Point Archaeological Site, about 10 minutes outside Fallon. If I was going to take a cue from the Stone Roses, it was to figure out what was “the one” here.

Post continues below …

There was once a lake at the edge of the Grimes Point archaeological site near Fallon, Nev. (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

Included at the Grimes Point site is a sheltered but barren rocky outcropping where ancient nomadic hunter-gatherers stored food. But this area looked dramatically different then. Lake Lahontan, part of a network of freshwater lakes that covered much of Nevada and western Utah during the previous Ice Age, would have dominated the adjacent landscape.

Eight-thousands years ago, animals flocked the marshy shoreline here. So too did Native Americans, who left behind petroglyphs and carvings in the rocks, even older than the ancient bristlecone pine trees I encountered in Great Basin National Park.

Looking out from this ancient spot, I tried to imagine how there was once a big lake out here. I could somewhat envision it. Nature can certainly be deceiving.

What is seen today out here is a lesson of climate change, a great force current civilization will be adapting to more and more in the coming decades. Water is the American West’s most precious resource and there’s precious little of it left out here. It’s no wonder that civilization flocks to water sources. Without it, civilization dries up. I didn’t want to linger for too much longer.

After I left the archaeological site in a cloud of dust, the last track from the Stone Roses album I was playing earlier started. It was “Fools Gold,” a song apparently inspired by the 1948 movie The Treasure of the Sierra Madre starring Humphrey Bogart, and the words did a good job summing up my feelings at the moment.

The gold road’s sure a long road / Winds on through the hills for fifteen days / The pack on my back is aching / The strap seams cut me like a knife

Fortunately I wasn’t shouldering an uncomfortable backpack on a foolish search for riches out in the desert. But my posterior was very much ready to not be driving. Roadtrips aren’t great for posture.