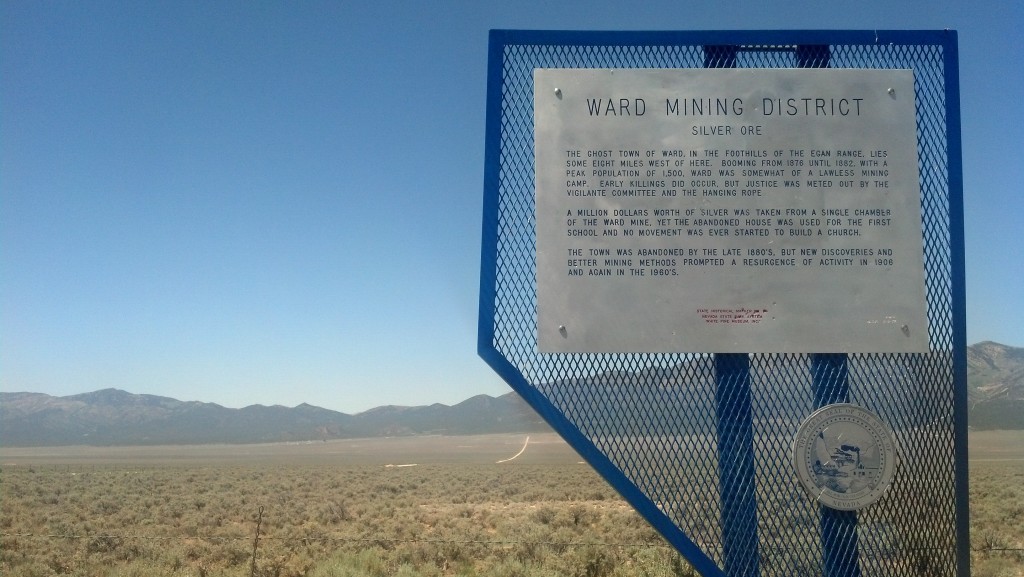

A historic marker near the ghost town of Ward, Nev., notes how the “vigilante committee and the hanging rope” helped keep the peace. (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

WARD, Nev. — In Travels With Charley, John Steinbeck wrote that “those states with the shortest histories and the least world-shaking events have the most historical markers. Some Western states even find glory in half-forgotten murders and bank robberies.”

For such an empty place, Nevada is full of historic markers. Many of the ones I encountered in the central part of the state — and I suspect elsewhere, too — celebrate the state’s rich mining heritage. The sign marking the ghost town of Osceola, northwest of Mount Wheeler in Great Basin National Park, notes how the nearby mining operations there once produced a gold nugget valued at $6,000. (I’m assuming that was a big deal at the time but nothing like the Comstock Lode.)

Closer to Ely, a marker off U.S. 93 celebrates the mining heritage of the ghost town of Ward, a place which was “booming from 1876 until 1882” before it was abandoned. Ward was a lawless place and from its description sounded like the type of settlement that could have inspired a John Wayne movie.

“Early killings did occur, but justice was meted out by the vigilante committee and the hanging rope,” according to the marker.

For the most part, there’s nothing left of these ghost towns. In the case of Ward, the roadside marker was miles from the actual site of the town, off-limits on the property of the modern-day mining operation. But Ward’s beehive-shaped charcoal ovens beehive-shaped charcoal ovens are certainly worth checking out.

Post continues below …

In these mining boom towns, charcoal was needed in the ore-smelting process.

According to the Las Vegas Review-Journal, these conical structures can be found elsewhere in the state, but in Ward, they’re both nicely preserved and accessible to travelers willing to drive off the main road. Ward’s ovens were constructed in 1876 by Swiss-Italian craftsman and are 30 feet high with a base diameter of 27 feet.

They could hold 35 chords of wood and produce 1,750 bushels of charcoal. After the ovens were abandoned, they were known to be used as places to seek shelter during inclement weather and “had a reputation as a hideout for stagecoach bandits,” according to the Nevada Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.

Post continues below …

To reach the charcoal ovens, you must drive roughly 10 miles through the desert on a gravel road. (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

For those running afoul of the law, this place is a good spot to hide. This abandoned settlement, which has its back to Ward Mountain, isn’t really on a road to anywhere. In order to reach the charcoal ovens, I had to drive along a gravel road off U.S. 93 for 11 miles through the desert.

It wasn’t necessarily too far from civilization — if an asphalt road through the middle of nowhere can be considered civilization — but it was far enough away where I felt somewhat vulnerable, especially since there was no cellphone reception. (I packed beef jerky and water in case of an emergency.)

On the final approach to the ovens, the six oddly shaped structures, lined up in a row, revealed themselves. They looked quite foreign to this landscape as if aliens hid them here where nobody could find them. (Area 51, the mysterious government facility long associated with reports of extraterrestrial activity, is roughly 200 miles away to the southwest.)

Before coming out this way, I envisioned the desert here to be something like the one where Chevy Chase’s Clark Griswold got lost and stranded in National Lampoon’s Vacation. I wasn’t too far off, but Ward is no Monument Valley. It’s more brown and green than it is brown and orange. There aren’t any weathered rock formations, only low mountain ranges that frame the horizon.

There are few signs of civilization or other living creatures out on the open range, but I did have to stop to let cattle cross the road at one point.

This is a place where drivers in passing cars acknowledge one another, since it’s unlikely another soul will come along anytime soon.

A few miles from the ovens, a dust-speckled black pick-up truck approached me and slowed down amid a huge plume of dust from the gravel road. The driver, an older gentleman in a white T-shirt waved and rolled down his window. I rolled down mine.

His very tanned skin had the complexion of broiled potato skins.

“Are you lost?” he asked.

“No, I don’t think so. I was just headed to the charcoal ovens,” I said.

“Ahh. OK. You’re here all the way from Virginia?”

“Actually, Washington, D.C.”

“Washington, D.C.?” His face winced in apparent disappointment. Perhaps I should have just left it simply as Virginia.

I was about to tell him about my whole Lincoln Highway adventure, but I stopped realizing that my earlier diversion to Great Basin National Park took me many miles off the original highway. It would be hard to explain.

“D.C. … Yep, that’s right,” I replied.

“Tell Barack Obama and Harry Reid I say hello,” he laughed. Perhaps he knew the president and Senate majority leader? I would never know. He rolled his window up without saying goodbye and drove off with the dust following him.

I got the sense that he thought I was foolish for coming out all this way. Perhaps I was. But there was no turning back now — especially with a one-way car rental.