GETTYSBURG, Pa. — I’ve arrived in the place that changed the course of the Civil War. I’ll be here for a few hours checking out some Lincoln-related sites, but before that, I want to detail the portion of the Lincoln Highway I drove a few weeks ago, between York and Philadelphia.

Although I drove this section from west to east, I’ll start in Philadelphia and work my way west back towards Gettysburg.

***

When you think of Abraham Lincoln, you don’t necessarily think of Philadelphia. But Lincoln traveled here a number of times before and during his presidency and through many of the towns the Lincoln Highway passes through between the City of Brotherly Love and Gettysburg.

According to the official Lincoln Highway map from the Lincoln Highway Association, the original route from New York City takes it into Center City right down Broad Street, Philadelphia’s primary north-south thoroughfare, to City Hall, where it heads west along Market Street, the city’s primary east-west thoroughfare, before linking up with Lancaster Avenue heading out of town.

I’ll start nine blocks east of City Hall at Philadelphia’s most recognized landmark, Independence Hall, on Chestnut Street between 5th and 6th streets.

This is a place you normally associate with the Founding Fathers, the Continental Congress and the Declaration of Independence from the 1770s. But Lincoln was here, too, albeit decades later.

Abraham Lincoln raises an American flag at Independence Hall in Philadelphia on Feb. 22, 1861. (Photo by Frederick De Bourg via the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

On his way from Illinois to Washington before his first Inauguration, Lincoln passed through Philadelphia and delivered a speech on Feb. 22, 1861.

At Independence Hall, Lincoln said:

I am filled with deep emotion at finding myself standing here, in this place, where were collected together the wisdom, the patriotism, the devotion to principle, from which sprang the institutions under which we live.

With the Union fracturing and mounting problems awaiting him in Washington, Lincoln spoke about the ideas that underpinned the Declaration of Independence and the difficult road ahead:

I have often pondered over the dangers which were incurred by the men who assembled here, and framed and adopted that Declaration of Independence. I have pondered over the toils that were endured by the officers and soldiers of the army who achieved that Independence. I have often inquired of myself what great principle or idea it was that kept this Confederacy so long together. It was not the mere matter of the separation of the Colonies from the motherland; but that sentiment in the Declaration of Independence which gave liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but, I hope, to the world, for all future time. It was that which gave promise that in due time the weight would be lifted from the shoulders of all men. This is the sentiment embodied in that Declaration of Independence. Now, my friends, can this country be saved upon that basis? If it can, I will consider myself one of the happiest men in the world if I can help to save it. If it can’t be saved upon that principle, it will be truly awful. But, if this country cannot be saved without giving up that principle—I was about to say I would rather be assassinated on this spot than to surrender it.

It was not Lincoln’s first time in Philadelphia. In 1848, Lincoln — then Illinois’ only Whig congressman — attended the Whig National Convention, being held in the Chinese Museum Building’s exhibition hall at 9th and Chestnut streets.

The Benjamin Franklin Hotel in Philadelphia occupies the site of where Lincoln attended the 1848 Whig National Convention and the hotel he stayed at on his way to Washington in 1861. (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

The building, according to “The Lincoln Trail in Pennsylvania: A History and Guide,” burned down on July 5, 1854, and was replaced with the Continental Hotel, where Lincoln stayed during his 1861 visit. It was also at the Continental Hotel where Lincoln was informed of the plot to assassinate him when he reached Baltimore. Lincoln also delivered a speech from the hotel’s balcony, where he said, according to “The Lincoln Trail in Pennsylvania”: “May my right hand forget its cunning and my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth if ever I prove false to those teachings” from the Declaration of Independence.

The Continental Hotel, one of the nation’s most prestigious hotels at the time, is long gone. On the site today is Benjamin Franklin Hotel.

Post continues below …

During my recent visit to Philadelphia, I stumbled across a giant mural of Lincoln, titled “A People’s Progress Towards Equality,” about a block to the east looming over a parking lot at 8th and Ranstead streets. It’s part of Philadelphia’s extensive Mural Arts Program.

“The Lincoln Trail in Pennsylvania” details a host of other sites related to Abraham Lincoln’s time in Philadelphia, including the sites of the various Philadelphia train stations Lincoln traveled through during his life, but let’s continue west toward Gettysburg.

***

Lancaster Avenue heads through West Philadelphia on its way out of town and at Girard Avenue, U.S. 30 links up with the Lincoln Highway route. I’ll be following U.S. 30 along the Lincoln Highway all the way into western Wyoming, with a few diversions along the way.

This route is the old Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike, regarded as the nation’s first long-distance engineered road and first major toll road. When it opened in 1795, it paved the road west, albeit paved with broken stone and gravel.

This road winds its way through Phialdelphia’s well-to-do Main Line suburbs, named for the Main Line of the Pennsylvania Railroad, which parallels the old turnpike west. When I think of Philly’s Main Line, I instantly think of Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant and James Stewart in “The Philadelphia Story.” This is their leafy, well-heeled turf, even though the great film doesn’t really have much to do with Philadelphia itself.

While the Lincoln Highway misses Valley Forge by a few miles, it passes through Paoli, the site of the infamous Paoli Massacre from the Revolutionary War.

Continuing west, the Lincoln Highway goes through Coatesville, a small industrial town that was the site of the infamous and horrifying 1911 lynching of an African-American mill worker named Zachariah Walker.

This history illustrates the truly shocking events of that day:

In a field just outside the borough of Coatesville, Walker was thrown into a hastily constructed fire. Three times he attempted to crawl out, only to be pushed back in until he moved no more. A crowd estimated between 3,000 to 5,000 men, women, and children witnessed Walker’s ordeal with a calm resolve.

After it was over, the crowd politely dispersed, though some lingered to collect body parts and other souvenirs before going back into town.

This terrible event led to a larger national debate on anti-lynching laws.

***

When most people think of Lancaster, Pennsylvania Dutch Country comes to mind. During my drive I saw a few Amish horse and buggies, but the Lincoln Highway route is fairly suburbanized heading toward town. Dutch Wonderland, a quirky amusement park east of Lancaster looks something more like Medieval Times. I’m sure it’s a fun time (for some), but I didn’t have time to take in the themed spectacle.

Lancaster promotes itself as the nation’s first major inland town. It’s a charming city, including its Central Market, which has been in operation for more than 275 years. It’s less hectic than Reading Terminal Market in Philadelphia but not as many vendors. The current Romanesque Revival building, dating to 1889, is a great architectural landmark. It’s a great place to stop off for a sandwich and stock up on Amish farm goods among other products, including a sinfully sweet maple bacon doughnut.

Post continues below …

The real reason for stopping off in Lancaster was to visit Wheatland, the home of President James Buchanan, the often-forgotten 15th chief executive who gladly handed the keys of White House over to Abraham Lincoln in 1861 as the Union was unraveling.

Buchanan had a somewhat famous dialogue with Lincoln upon entering the White House. The exact wording of the quote varies slightly depending on the source, but it goes something like this: “Sir, if you are as happy in entering the White House as I shall feel on returning to Wheatland, you are a happy man indeed.”

Post continues below …

In this display at the Lancaster County Historical Society, you can see a Conestoga wagon at top and a Lincoln Highway sign post at right. (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

If you’re ever in Lancaster, you should visit Wheatland, which sits just outside downtown adjacent to the Lancaster County Historical Society, where you can learn so much more about the area, including the production of Conestoga wagons, which were so important in American expansion westward. When I have some downtime in Pittsburgh later this week, I’ll dig into Buchanan’s life and legacy in greater detail.

After reading a Buchanan biography and conducting some additional research, it’s clear that to understand the Lincoln presidency and the road that lead to the Civil War, you must understand James Buchanan. He’s a fascinating figure and an ultimately flawed leader. But more on that later.

It’s time to continue west on the highway.

***

Looking out over the Susquehanna River valley near Wrightsville, Pa., at Samuel S. Lewis State Park. (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

West of Lancaster lies the great Susquehanna River. The town of Columbia, home to the National Watch and Clock Museum, was the western terminus of the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike and the original railroad from Philadelphia, which connected to the Pennsylvania Canal, part of a network of canal and railroad links designed link Pittsburgh with Philadelphia and keep Pennsylvania economically competitive with New York’s Erie Canal.

The area where Columbia and Wrightsville, which sits across the river, are, was at one point under consideration to be the nation’s capital. At Samuel S. Lewis State Park, which overlooks the valley to the southwest of Wrightsville, you can take in the impressive geography. This area would have been an impressive setting for the U.S. capital if this site got a few more votes.

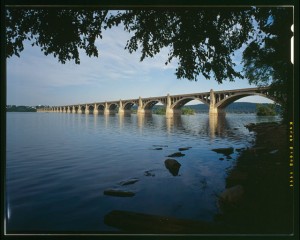

The Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge in 1997 (Photo by Joseph Elliot via the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

Bridges have crossed this broad river since 1814, making this area strategically important. Just before the Battle of Gettysburg, Union forces burned the bridge, which prevented invading Confederate forces from crossing the Susquehanna and onward toward Lancaster and Philadelphia.

Today’s bridge, which is 7,374 feet long, was an engineering landmark when it opened in 1930. It has 28 arches, 100,000 cubic yards of concrete and 8 million pounds of steel reinforcing rods. Oddly enough, when you drive over it, you really can’t see the river itself.

Although U.S. 30 was realigned and improved to an expressway bypass north of the Columbia-Wrightsville Bridge, the Lincoln Highway continues along the original road to York, today’s PA-462, and onward to Gettysburg.

Pingback: The Great Platte River Road Begins | The Lincoln Highway Guide

Pingback: The All-Important Echo Canyon | The Lincoln Highway Guide