UPPER SANDUSKY, Ohio — For my Lincoln Highway trek across Ohio, I’ve stuck primarily to U.S. 30. But there are various alignments of the route across this part of north central Ohio. Instead of the more modern alignment, I could have taken a more southerly route via Lima and along one of the most notorious reroutings of the highway.

A Lincoln Highway marker stands just to the east of the center of Upper Sandusky, Ohio (Photo by Michael E. Grass)

According to a 2004 historic assessment of the Lincoln Highway by the National Park Service:

One of the most controversial reroutings of the Lincoln Highway came when the [Lincoln Highway Association] dropped 70 miles of roadway between Galion and Lima via Marion and Kenton in favor of an unfinished rout to the north. This occurred a mere three weeks after these towns celebrated their inclusion on the Proclamation Route of 1913. An unsuccessful petition asking the Lincoln Highway Association to reverse the rerouting was supported by then Senator Warren Harding, which ultimately let to the building of the Harding Highway along the route abandoned by the Lincoln Highway.

There’s a Harding Highway? You learn something new everyday.

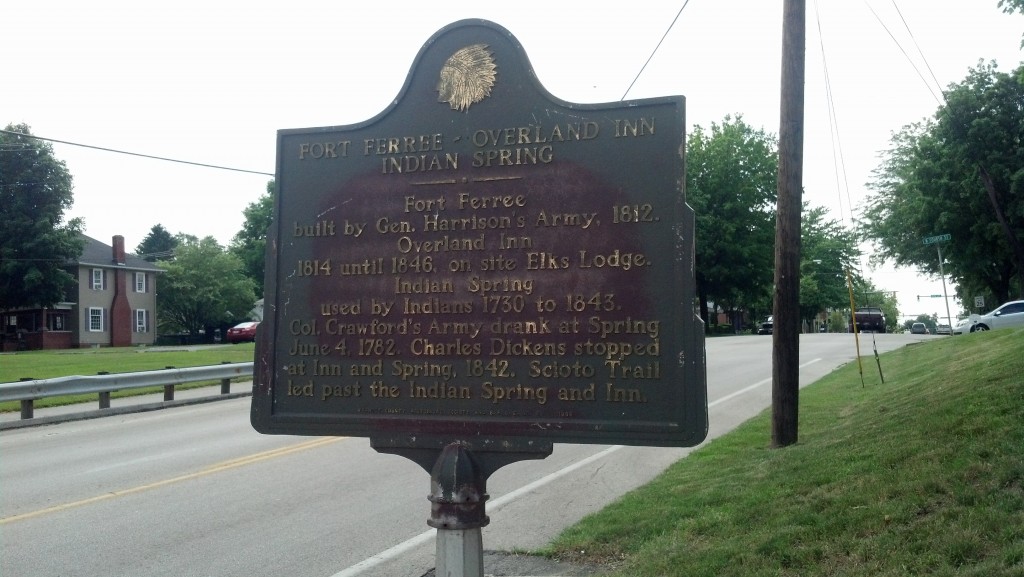

Back in Upper Sandusky, the Lincoln Highway passes an Elks Lodge at E. Wyandot Avenue and 4th Street with an aging historic marker out front that sits opposite a brick Lincoln Highway column across the road.

There’s a spring on the property with a storied past, including ties to Charles Dickens. The English author visited this area just before the Wyandotte Indians, who had long-standing settlements here, became the last Native American group to leave Ohio after heading west to a reservation in Kansas in 1842.

In Chapter 14 of American Notes, Dickens detailed his time here:

It is a settlement of the Wyandot Indians who inhabit this place. Among the company at breakfast was a mild old gentleman, who had been for many years employed by the United States Government in conducting negotiations with the Indians, and who had just concluded a treaty with these people by which they bound themselves, in consideration of a certain annual sum, to remove next year to some land provided for them, west of the Mississippi, and a little way beyond St. Louis. He gave me a moving account of their strong attachment to the familiar scenes of their infancy, and in particular to the burial-places of their kindred; and of their great reluctance to leave them. He had witnessed many such removals, and always with pain, though he knew that they departed for their own good. The question whether this tribe should go or stay, had been discussed among them a day or two before, in a hut erected for the purpose, the logs of which still lay upon the ground before the inn. When the speaking was done, the ayes and noes were ranged on opposite sides, and every male adult voted in his turn. The moment the result was known, the minority (a large one) cheerfully yielded to the rest, and withdrew all kind of opposition.

We met some of these poor Indians afterwards, riding on shaggy ponies. They were so like the meaner sort of gipsies, that if I could have seen any of them in England, I should have concluded, as a matter of course, that they belonged to that wandering and restless people.

After the Wyandotte Indians left this place, the village of Upper Sandusky was laid out and became the county seat of Wyandot County (note the different spellings), named in honor of the former inhabitants.

Thus far on my Lincoln Highway journey, I haven’t encountered much history related to Native Americans until I reached Upper Sandusky. That, for sure, will change as I continue westward.